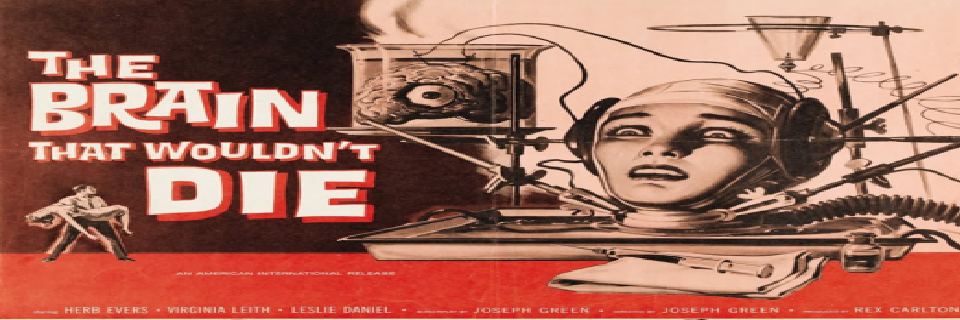

The Brain That Wouldn’t Die, a 1962 science fiction horror film directed by Joseph Green, presents a bizarre and unsettling tale of scientific ambition, moral decay and the grotesque consequences of tampering with nature. With a pulpy, low-budget style and an atmosphere of grim curiosity, the film explores the extreme lengths to which a man might go in the name of love and scientific progress, ultimately revealing a dark parable about obsession, identity and the ethics of experimentation.

The story revolves around Dr Bill Cortner, a brilliant yet reckless surgeon who works alongside his father in a prestigious medical facility. While his father adheres to traditional medical practices and ethical constraints, Bill is increasingly absorbed in his own experiments, particularly in the area of transplant surgery. He believes that the boundaries of life and death can be pushed far beyond what the medical community deems possible. Behind his father’s back, he conducts unauthorised operations in a private laboratory, secretly harvesting limbs and organs with the aim of perfecting full-body transplants.

Bill’s work takes a horrific turn when he and his fiancée, Jan Compton, are involved in a car accident. The crash is violent and catastrophic, with Jan apparently killed on impact. In a moment of deranged resolve, Bill retrieves her severed head from the wreckage and rushes it back to his hidden lab, determined to preserve her brain and ultimately find a new body for her. Using a mysterious experimental serum, he succeeds in keeping Jan’s head alive in a tray of chemicals, sustained by tubes and machinery in the eerie confines of his underground facility.

Jan, now reduced to a disembodied head, regains consciousness and quickly realises the horror of her situation. She is at first disoriented, but soon becomes resentful, appalled at Bill’s decision to prolong her life in such a grotesque form. Her voice echoes with despair and anger, and she pleads for death. Bill, blinded by his obsession and convinced that he can restore her to a better existence, ignores her pleas and becomes consumed with the task of finding a new body.

As Jan lies trapped and helpless, her situation becomes increasingly tragic. Her isolation leads to a psychic awakening, and she begins to communicate telepathically with another of Bill’s failed experiments locked behind a heavy door in the laboratory. This unseen creature, the result of an earlier botched transplant, is a monstrous presence that grunts and growls, a physical embodiment of Bill’s failures and hubris. Jan’s bond with the creature grows, and it becomes clear that she sees it as a potential ally in her rebellion against the man who imprisoned her.

Meanwhile, Bill scours the city for a suitable female body. His selection criteria are superficial, based largely on physical beauty. He visits strip clubs and modelling agencies, evaluating women like a butcher selecting meat, entirely indifferent to their personalities or lives. His gaze is cold and clinical, revealing the depth of his dehumanisation. Eventually, he targets a model named Doris, who has body image insecurities due to a facial scar. Bill manipulates her vulnerability, promising surgical restoration while secretly planning to murder her and transplant Jan’s head onto her body.

Back at the laboratory, Jan’s frustration and fury deepen. Her dialogue becomes increasingly philosophical and accusatory, questioning not only Bill’s ethics but the nature of identity and the soul. She confronts the very idea of whether existence without agency or physical autonomy can truly be called life. Her transformation from victim to vengeful intellect becomes a central arc in the film, and her resolve to destroy Bill and end her own suffering forms the emotional heart of the story.

The climax occurs when Bill brings Doris to the lab under the guise of performing corrective surgery. As he prepares to execute his plan, Jan psychically urges the creature behind the door to break free. With explosive force, it bursts out and attacks Bill, mauling him in a violent frenzy. The chaos disrupts the operation, and Doris escapes unharmed. The creature, now free, turns its wrath on the man who created it, while Jan, still a head in a tray, watches with grim satisfaction.

In the final moments, the laboratory burns as the result of the struggle. Jan, accepting her fate, chooses to perish in the fire rather than continue her unnatural existence. Her last words are tinged with relief and release, bringing a sombre end to the harrowing ordeal. The creature, now avenged, disappears into the flames, leaving the audience with a lingering sense of horror and poetic justice.

Visually, the film is stark and minimal, its sets and lighting creating a claustrophobic and unsettling mood. The laboratory, with its crude equipment, flickering lights and grotesque medical instruments, reinforces the atmosphere of twisted science and unchecked ambition. The film’s special effects, though rudimentary by modern standards, convey a visceral sense of unease. The image of Jan’s severed head, blinking and speaking from her tray, remains one of the most iconic and disturbing in 1960s horror cinema.

Thematically, The Brain That Wouldn’t Die functions as a cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific arrogance. Bill’s descent into madness is not driven by malice but by his belief that he can conquer death and perfect life. In doing so, he loses all empathy and humanity, reducing the people around him to objects in his experiment. Jan’s transformation from helpless victim to moral voice exposes the inhumanity of his actions and forces the audience to confront the consequences of treating life as a mechanical puzzle rather than a sacred phenomenon.

The film also explores gender and power in subtle, though dated, ways. Bill’s fixation on physical beauty and his disregard for consent or identity in choosing a new body for Jan highlight a chilling objectification of women. Jan, despite her physical helplessness, ultimately reclaims power through her intelligence and will. Her alliance with the creature symbolises a rebellion of the discarded and deformed against the authority that exploited them.

While the film may lack polish and narrative finesse, it compensates with atmosphere, thematic ambition and a uniquely macabre vision. Its blend of science fiction and body horror taps into fears about medical experimentation, the limits of human control and the existential dread of consciousness separated from the body. In the end, The Brain That Wouldn’t Die delivers a haunting meditation on the costs of playing god, and the tragic futility of attempting to outwit nature with arrogance in place of understanding.