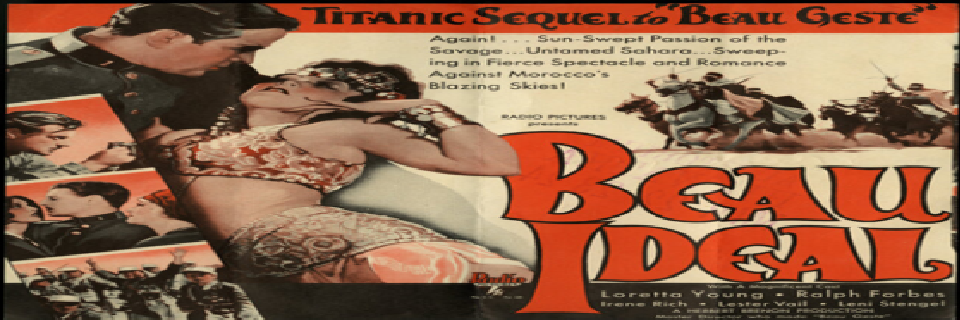

Beau Ideal, released in 1931 and directed by Herbert Brenon, serves as a sequel to the 1926 silent film Beau Geste, both adaptations of P.C. Wren’s novels. This early sound film intertwines themes of friendship, honour, and redemption against the backdrop of the French Foreign Legion in North Africa.

The narrative commences in a desolate desert, where two soldiers, known only as Smith and Brown, are confined in a grain pit, awaiting death. As they converse, they realise they are childhood friends: John Geste and Otis Madison. This revelation triggers a series of flashbacks to their youth in England, highlighting their close bond and mutual affection for Isobel Brandon.

Years later, Otis returns to England, discovering that John has joined the French Foreign Legion and that Isobel is betrothed to him. Determined to reunite with his friend and perhaps win Isobel’s heart, Otis enlists in the Legion, hoping to find John and bring him back home.

Otis’s journey leads him to a desert fort, where he is assigned to a penal battalion. Through a series of events, he is falsely accused of mutiny and ends up in the same grain pit as John, bringing the story back to the present.

Their dire situation takes a turn when they are rescued by a band of Arabs. However, the rescue is a ruse; the Arabs intend to use them as bait to lure their fellow legionnaires into a trap. Zuleika, the Emir’s consort known as the “Angel of Death,” becomes enamoured with Otis. She informs him of the impending ambush and aids in their escape.

John and Otis race back to the fort, warning the garrison and helping to repel the attack. Their bravery earns them exoneration and freedom. With Zuleika’s affections now directed towards Major LeBaudy, Otis is released from any obligation to her. Returning to England, John relinquishes his claim to Isobel, allowing Otis and her to pursue a future together.

Despite its adventurous plot, Beau Ideal was not a critical or commercial success. Critics cited issues with the film’s pacing, dialogue, and performances. However, it did introduce certain technological advancements in sound and visual effects, marking its place in early cinema history.

Thematically, the film centres on loyalty, moral conflict, and transformation. Otis Madison undergoes a significant journey of self-discovery, leaving behind his life of privilege to experience hardship in the desert. His desire to rescue his friend evolves into a deeper understanding of sacrifice and personal growth. Through suffering and service, both Otis and John come to realise the true value of honour and friendship, independent of social expectation or romantic rivalry.

The visual presentation reflects the stark conditions of desert warfare. The cinematography, though constrained by early sound technology, manages to evoke the harshness of the environment and the isolation felt by the characters. The sequences in the grain pit are especially tense and claustrophobic, providing a sharp contrast to the vastness of the desert scenes that follow. The atmosphere is one of persistent adversity, which underscores the mental and physical toll endured by the legionnaires.

Zuleika’s role introduces an exotic and dramatic element to the film. She straddles the line between danger and salvation, motivated by passion yet capable of mercy. Her assistance, though initially born out of desire for Otis, ultimately enables the heroes to foil the enemy’s plan. In this regard, her character departs from typical portrayals of villainous femme fatales of the period, offering a more nuanced depiction of power and influence.

Isobel, though central to the emotional tension between Otis and John, remains largely peripheral in terms of screen time and narrative depth. Her character represents an idealised domestic life, far removed from the violence and moral ambiguity of the Legion. It is Otis’s decision to return to her, after having confronted death and disgrace, that provides closure to his journey. John’s selfless act of stepping aside further elevates the film’s core message: that true friendship and integrity are more lasting than fleeting desires or social conventions.

While Beau Ideal struggles at times with its tonal shifts and the limitations of early sound film-making, it nonetheless aspires to combine romance, action, and ethical reflection. Its depiction of the Legion is less focused on jingoism and more concerned with personal evolution. The uniformed setting becomes a crucible in which character is tested and redefined.

The film also contrasts the illusions of youthful dreams with the grim realities of adult life. The early scenes in England, full of promise and genteel ambition, are quickly overshadowed by the grimness of desert punishment and military injustice. Otis’s initial romantic idealism is gradually dismantled, replaced by a deeper resilience and understanding forged through trial. By the end, the characters are changed, not through dramatic triumphs but through quiet decisions and hard-earned maturity.

Though not widely celebrated today, Beau Ideal offers an intriguing look into early 1930s cinema, where the transition from silent film to sound was still finding its rhythm. The performances, particularly by Lester Vail and Ralph Forbes, convey a sincere if sometimes stagey intensity typical of the era. Their dynamic captures the push and pull of masculine loyalty and competitive affection, framed within a narrative that values redemption over revenge.

In conclusion, Beau Ideal reflects both the ambitions and the limitations of its time. It attempts to bridge the gap between sweeping adventure and intimate moral storytelling, set against the exoticism and brutality of Foreign Legion lore. Though flawed in execution, the film remains a notable entry in the genre for its earnest engagement with questions of loyalty, identity, and the cost of ideals.